The library's take on the modern house

The new Woollahra Library at Double Bay, designed by BVN, opened last year. At first glance, this place is strangely lacking in books; instead, there’s lush greenery, a broad central staircase used more for sitting on than for walking up, computer terminals and – controversially – a slippery dip for the kids. No ‘Quiet, please’ signs in sight.

It’s all a bit confronting to those of us who like the old-fashioned rows of books with their own special library smell, and don’t even mind the slightly cranky librarians found in such establishments.

But we’d have to say one of the enormous benefits of the digital world is that much of the material within libraries is now online, and available to all of us at any time of the day or night. Nowhere is this more evident than at the State Library of New South Wales which, for a number of years, has gradually been digitising its collections. Unsurprisingly, given how much is contained within those walls, this is an ongoing, and vastly complex, project.

Beaufort Home construction photographs / Arthur Baldwinson collection. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

An armchair look at modern houses

To look at one tiny part of it – for anyone interested in Australian architecture and modern house design, the State Library’s collection is far-reaching, endlessly revealing and often surprising. It’s possible, without stepping into the buildings on Macquarie Street, to view sketches, architectural drawings, plans, photographs and even such unexpected items as Harry Seidler’s ‘internment camp shirt from Quebec, Canada, 13 July 1940 – 4 October 1941’ which, along with many other personal and professional items, was given to the library by the architect. It’s described in the catalogue as having ‘a red circle sewn on reverse and “SS Guaranteed by Sigal quality Garments size 15” on label inside collar’.

Getting lost in the collection

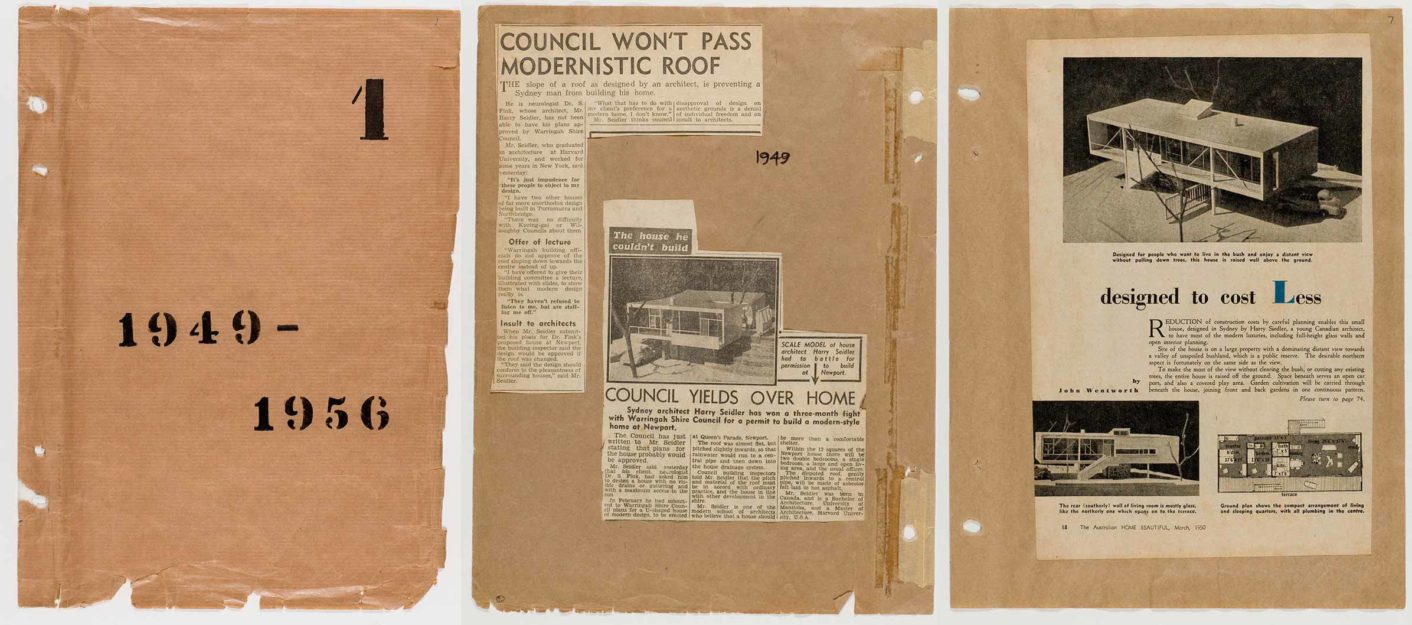

Seidler’s early scrapbooks of press cuttings, staples evident on the page and cuttings slightly skewiff, are there, too – it’s almost too easy to access the yellowing clippings of the day and get lost in contemporary stories either praising his work or chronicling his battles with local councils. A 1949 clipping has the headline ‘Council Won’t Pass Modernistic Roof’; on the same page and for the same house, another headline reads ‘Council Yields Over Home’. Look at another clipping and you’ll find that after one victory over Kuring-gai Council’s exception to a modern house he was planning in Roseville, Seidler was reported as saying, “The council should spend its money on constructing roads and playgrounds, instead of passing completely idiotic judgments on a professional man’s work.”

Hugh Buhrich, who designed an idiosyncratically modern house in Castlecrag, is represented, too, by his scrapbooks (thank goodness for the pre-digital age, and thank goodness, too, for the digital technology to reproduce these relics). Within the pages, you can read, for instance, his defence of glass, in an article he wrote for The Sydney Morning Herald in 1958, decades before indoor-outdoor living became the norm. It starts: “A lot of reasons have been given recently why glass should not be used in modern houses, but nobody has yet mentioned why it should be used as a whole continuous wall and not just a window.”

Harry Seidler scrapbook of press cuttings, 1963-1968. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Finding the iconic and the unbuilt

Check out the digital content on early modernist Arthur Baldwinson, and in no time at all, you can browse through construction photos of the Beaufort Home. The photos alone are worth looking at, and their presentation, on album pages with titles added by manual typewriter, is a distinct bonus.

While you’re making your way through the digital content of architects and architectural drawings, you may find yourself engrossed in material on the Sydney Opera House. Or then again, you may just stumble on early sketches of a modern house, four proposals for which went to Warringah Council. The sketches give some idea of how the architect’s mind worked, something we could never get from the finished house, because it doesn’t exist. When the architect was ready to build, he was out of a job – it’s Utzon’s own house in Kara Crescent, Bayview.